For the times we live in, Lalan’s legacy and his songs are rays of hope. Lalan’s songs are great tools to construct cultural history, no doubt. But his songs can also be sung when reason loses its way in our conversations and actions. Instead of arguing over good and bad in our religions and castes, which does no good, we should consider singing his songs with all our neighbours and establish harmony in our relations parallelly with rhyme and rhythm. His songs can be channels through which man can connect with himself and others.

To read full article, click: TISC Student Column – Lalan Fakir: His Songs and Philosophy by Mucheli Rishvanth Reddy or read below

In another hand

Lies the key to my house,

How will I unlock, to gain

The treasures within…

– From ‘The Fakir’.

Folklore is one of the greatest repositories of India’s cultural past. They are ‘outpourings from the heart’[i] of native people. Mostly all folklore are oral traditions, which are sung by men and women together, in their work, leisure and recreation. They passed from one generation to another, evolving, and a part of it being lost after every generation.

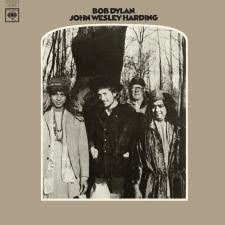

Indian folklore is of great use for historians and sociologists to construct the people’s traditions, customs, and their pasts. Folklore influenced not just academicians, but also singers and songwriters from across the world. One such influence can be seen in Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan’s eighth studio album John Wesley Harding. On the cover of this album[ii] (in the photo below), standing next to Dylan are Laxman Das Baul and Purna Das Baul. Laxman and Purna Das Baul are popular musicians in Baul tradition. The Baul folklore tradition is seen in the Bengal region and in Bangladesh. Baul was recognised in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008[iii].

Influences of this tradition can be seen in works of another Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, and Bangladeshi National Poet Kazi Nazrul Islam. American Author Edward C. Dimock called Tagore as ‘The Greatest of The Bauls of Bengal’. Tagore is known as the “discoverer” of Baul songs, who with his discovery “added greatly to the wealth of Bengali literature”[iv]. Acknowledging his love for Bauls, Tagore wrote[v]:

One day I chanced to hear a song from a beggar belonging to the Baul sect of Bengal…. What struck me in this simple song was a religious expression that was neither grossly concrete, full of crude details, nor metaphysical in its rarified transcendentalism. At the same time, it was alive with an emotional sincerity. It spoke of an intense yearning of the heart for the divine which is in man and not in the temple…. Since then I have often tried to … understand [these people] through their songs, which are their only form of worship. One is often surprised to find in many of their verses a striking originality of sentiment and diction; for, at their best, they are spontaneously individual in their expressions.

I have expressed my love toward the Baul songs in many of my writings…. I have fitted the tunes of the Bauls to many of my songs, and in many other songs the tunes of the Bauls have consciously or unconsciously been mixed up with other musical modes and modifications…. The tune as well as the message of the Bauls had at one time absorbed my mind as if they were its very element.

This Baul tradition became extremely popular because of compositions made by one of the most celebrated saints, Lalan Fakir. Most of the Baul compositions which Tagore fitted in his writings were originally composed by Lalan Fakir. At the beginning of his novel Gora, which is considered as his masterpiece, Tagore presented these lines:

Into the cage flies the unknown bird,

It comes I know not whence.

Powerless my mind to chain its feet,

It goes I know not where.

These lines were actually composed by Lalan Fakir. “It was in fact Rabindranath Tagore’s enthusiasm for Lalan’s songs that helped diffuse the tradition amongst the elite”[vi]. This great man, Lalan Fakir is a largely forgotten figure now. But his songs were sung by generations after generations, and continues to keep the Baul tradition popular. As “time passes, his songs become part of folklore, but the man himself remains shrouded in mystery”[vii]. Lalan doesn’t know how to read or write. He learned about all the religions through what he saw and heard in conversations with people. No one knew, Lalan himself included, from where he got the inspiration to sing.“Perhaps he would be conversing with his friends, or immersed in his own work, when a rapture seized him and with it emerged the words of a song. At such times, words swan into his mind like shoals of baby rui in the river and tunes tumbled out in glorious unison. So when Lalan felt a new song welling up within him, he would call out, ‘Who’s there, the ruis are flooding my mind, they’re coming, they’re coming!’”. It is his abled followers who remembered his songs and passed it over to other people. At times when his followers sang songs composed by Lalan in his presence, Lalan would surprisingly ask if he is the one who composed it. Lalan was completely free from any attachments. But his ears were always close to the ground and he captured the universal truths and wisdom in his songs.

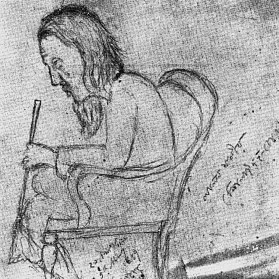

There are not many authentic records on the life and times of Lalan Fakir. The only available portrait of Lalan Fakir in his lifetime is a sketch drawn by Jyotirindranath Tagore (picture below)[viii], elder brother of Rabindranath Tagore.

But what is certain is his legacy, which is very much felt in Bengali literature. He was born in nineteenth-century Bengal, when caste oppression was at its zenith, women were looked down upon in society, even though abolished by British, Sati was widely practised in villages, and religious conflicts – immense. Common people were exploited by Zamindars and other officials. Lalan Fakir set out to create a world where people could lead a simple and peaceful life without being exploited or divided. The weapon with which Lalan Fakir sought to attain his objective was through singing songs.

He is a relevant figure for the times we live in, when relations between human beings are becoming more and more fragile every day and divisive forces, like caste, religion, and colour are deepening between people. Bengali Novelist and Poet Sunil Gangopadhyay wrote a brilliant fictional biography of Lalan Fakir titled ‘The Fakir’, which majorly explores the philosophy of Lalan Fakir. In the following essay, I presented excerpts from his work to establish a definite picture of Lalan’s philosophy as presented in the novel.

In the introduction to his novel, Sunil Gangopadhyay pointed out that “Lalan did not subscribe to any conventional religious thought and abjured all religious rituals, believing instead in the Humanistic doctrine of the centrality and validity of Man. His unconventional attitude earned the ire of both orthodox Hindus and Muslims but attracted a large following among poorer sections of society. At the time of his death, it was estimated that he had around ten thousand followers”.

Lalan questioned everything in this nature. He tried to understand the logic behind established rules and norms laid down by religion and caste. One day, he would look at the sky in the forest and question himself – “How vast it stretched, what worlds did it contain? Could there be truth in the belief of a divine city there, a Hindu heaven, or a Muslim paradise? Had anyone been there and returned to tell others about it? Did this land of gods have towns and bazaars for their needs? Which side did Allah live in? And what about the Christians? Lalu [Lalan Fakir] once heard a Christian missionary preaching… about how Christ was the son of God. Did that mean that Christ’s father was the one true God? What was his name?”

Lalan was troubled by religious practices. “What is religion? Did man exist merely for religion, or did religion exist for man? Could a man who had shunned religion, then, have no right to live?”. He wanted to run away to a place where these divisive forces wouldn’t trouble him anymore. But is there such a place? “Everywhere I see men divided according to religion, into Hindus and Muslims and Christians, men and women who perhaps might have lived in peace and yet are trapped by the burden of their faith! Everywhere, I see passions raising, swords being drawn, and futile battles raging over the gods one worships”. Lalan thought that there is a place beyond all this. It is in “the forests, there are birds and animals not cloven into caste and faith. I will go and live with them”.

He established a small settlement in a forest, whose lands were owned by the Tagores, where anyone outcasted by the society could come and live and practise any faith they wanted. Lalan said, “I was a Hindu once, perhaps I’m a Muslim now, or even a Christian…. I respect religions but not their divisive rules, just as I recognize different communities but not the segregation of anyone. Do you know what my heart tells me? That we are all men first and foremost, and that is what we should believe. You can follow all the rituals of any religion you choose and find peace of mind there. Alternatively, you can give up all rituals, all worship, and find faith in the love of mankind and lead a blissful life”. This pragmatic approach brings to mind Blaise Pascal’s Wager: “If you believe in God, Pascal had said, and He turns out to exist, then you have obviously made a good decision; however, if He does not exist, and you still believe Him, you haven’t lost anything; but if you don’t believe in Him and he does exist, then you are in serious trouble”. Lalan expressed his ideas in a song:

People ask, what is Lalan’s faith?

Lalan thinks, I’ve not seen the face

Of Faith with my eyes!

Some sport a garland and some the tasbi,

And with that they slice themselves apart.

But when it is time to be born or die

What tells them apart?

If circumcision makes a Muslim man,

Is the body a token of one’s faith?

A Brahmin has a Holy thread;

But what about the Brahmin women?

The world is alive with talk of faith

Men find salvation and fame in it

Lalan has torn such faith into shreds

And left it by the old trodden paths!

According to Lalan, the quest for mankind should be discovering oneself. This quest alone can bring realisation to man and cleanse him of all the evil within him. Lalan said, “I am a humble man, I do not know what I seek. But I know that man is the supreme being and this body of ours contains the whole universe, a wonderful kaleidoscope that holds the greatness of Creation. Sometimes, I can feel within this machine some inner being, deep within me, but to hold on to him is difficult, he is elusive, he slips out of my grasp”. He sang:

When will I be united?

With the Being of my Heart?

Lalan’s philosophy gave importance to man, and not to any of his attributes that are ascribed with his birth like caste or religion. He “privileged the human being over any narrow religious identity”. For him, mortal men and women are free beings and wonderful creatures. People can lead a peaceful life if they realise that “man is the ultimate truth, there is nothing above him”. Lalan sang:

Will there be such a birth ever?

Live to the full in this glorious stream of life.

Infinite are the shapes of Sai,

For I hear that mankind is the truth above all.

Even the Gods pray

To be reborn as mortals.

Good fortune of many births

To be born a mortal on this glorious shore.

This was a very unconventional philosophy at a time when people were made to believe that it is only through religion that one can achieve salvation. Lalan Fakir’s greatest contribution with his songs is to show that salvation being “a personal journey [is] independent of the dictates of conventional religion”.

We live in a time where religious fundamentalism and communalism are gaining strength, caste is still a major social problem dividing people, and marginalisation of minorities is rampant. For the times we live in, Lalan’s legacy and his songs are rays of hope. Lalan’s songs are great tools to construct cultural history, no doubt. But his songs can also be sung when reason loses its way in our conversations and actions. Instead of arguing over good and bad in our religions and castes, which does no good, we should consider singing his songs with all our neighbours and establish harmony in our relations parallelly with rhyme and rhythm. His songs can be channels through which man can connect with himself and others.

Oh peacock, oh cuckoo, do come and see

Within my empty house, the Divine Play in me..

References

[i] Literature & Folklore. (n.d.). Retrieved from Ministry of Culture, Government of India: http://www.indiaculture.nic.in/literature-folklore

[ii] https://www.bobdylan.com/albums/john-wesley-harding/

[iii] https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/baul-songs-00107

[iv] Edward C. Dimock, Jr. (1959, Nov). Rabindranath Tagore–“The Greatest of the Bauls of Bengal”. The Journal of Asian Studies, 19(1), 33-51.

[v] As quoted in Edward C. Dimock, Jr. (1959, Nov). Rabindranath Tagore–“The Greatest of the Bauls of Bengal”. The Journal of Asian Studies, 19(1), 33-51.

[vi] Gangopadhyay, S. (2010). The Fakir. (M. Mitra, Trans.) New Delhi: Harper Perennial.

[vii] Gangopadhyay, S. (2010). The Fakir. (M. Mitra, Trans.) New Delhi: Harper Perennial.

[viii] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fakir_Lalon_Shah.jpg

Leave a comment